Byzantine Fault Tolerant ordering servic for Hyperledger Fabric

- Feature Name: (SmartBFT ordering service)

- Start Date: (TBD)

- RFC PR: (leave this empty)

- Fabric Component: (mostly the orderering service)

- Fabric Issue: (leave this empty)

Table of contents

- Summary

- Background

- BFT Consensus Library

- The SmartBFT ordering service

- Possible questions and their answers

Summary

This RFC amends the SmartBFT RFC from 2020 by addressing the concerns raised in the corresponding discussion. It builds upon two additional earlier RFCs: An RFC that deals with block verification and replication, and an RFC that deals with inversion of control in the orderer codebase.

The RFC gives motivation to why we should integrate the SmartBFT consensus library into Fabric, gives an overview of the SmartBFT consensus library, and then suggests a way to make a Fabric ordering service that incorporates the library.

The proposal heavily draws upon the publicly available fork of Fabric that is known to already by in use by some commercial companies.

Technical details about the SmartBFT-Go consensus library can be read in the paper “A Byzantine Fault-Tolerant Consensus Library for Hyperledger Fabric” which appeared in IEEE International Conference on Blockchain and Cryptocurrency 2021.

The SmartBFT consensus protocol is inspired by the BFT SMaRt paper, hence its name. Its core consensus protocols (total order agreement, view change) follow the paper, but it also has enhancements that improves its operation in a production setting, such as heartbeats to ensure leaders that are faulty are detected early even if there are no pending transactions. For more information about the protocol see the relevant section.

Background

Difference from RFC 006-bft-based-ordering-service

This RFC is heavily based on the first ordering service RFC submitted to the Fabric RFC repository, and it proposes a design of how to integrate the SmartBFT consensus library into Hyperledger Fabric orderers. Unlike its precursor, it doesn’t aim to define the following aspects:

-

How block signatures are validated

-

How orderers and peers learn about new blocks being formed from other orderers.

The above two aspects are explained in a separate RFC.

Another notable difference from the original SmartBFT RFC is that this RFC adheres to the changes to be introduced in the Ordering service framework RFC. Specifically, unlike the original SmartBFT RFC, this RFC does not propose to implement a BFT consensus plugin, and instead, it follows the spirit of the Ordering service framework RFC and suggests implementing a single orderer binary that only runs SmartBFT chains.

Byzantine Fault Tolerance and Fabric

One of the fundamental properties of a blockchain, be it permissioned or permissionless is achieving a total order of transactions across all nodes.

Achieving total order in blockchains is done by having nodes participate in a consensus algorithm, where nodes input to the algorithm a set of transactions, and the algorithm makes all nodes receive back an ordered subset of the transactions.

There are various types of consensus algorithms, and they differ not only in what is done but also in the assumptions on the extent of which nodes may deviate from the algorithm.

In a Crash Fault Tolerant (CFT) consensus algorithm, the assumption is that each node follows the protocol unless it crashes or is unreachable.

A more involved setting is where nodes may not only crash but may also behave arbitrarily. In such a model, the nodes may send other nodes conflicting messages, lie about events they have observed, collude with other nodes and also sign conflicting votes. In such a setting, it is crucial to run a Byzantine Fault Tolerant protocol that can withstand corruption of a subset of the nodes. Otherwise, some peers may be misled to believe a version of the world state, while other peers, a different version. Such a situation may lead to double spending funds or to total service termination.

Hyperledger Fabric and BFT consensus

Hyperledger Fabric is one of (if not the most) most popular permissioned blockchain platforms as of today.

Yet, surprisingly and regrettably it lacks what every other competitor of it possesses, which is Byzantine Fault Tolerant consensus.

Even though requirement for a BFT ordering service was raised early on, in 2016, Fabric still lacks what is often described as a key component of a blockchain, be it permissioned or permissionless.

BFT Consensus Library

This proposal suggests to incorporate the SmartBFT consensus library into Hyperledger Fabric. Despite being developed as a consensus library for Fabric, the SmartBFT consensus library is blockchain agnostic, and can be used for any application that requires total order of transactions.

The protocols implemented by the library

In the SmartBFT consensus protocol, the parties that participate in the protocol are termed “nodes”, and they receive transactions from clients to be totally ordered and atomically broadcasted among themselves. As in the original PBFT paper, each batch is eventually given a sequence in the current view, and the nodes advance to a higher view when the leader of the current view is considered faulty. However, unlike the PBFT protocol, the SmartBFT library does not deal with updating clients about their requests being ordered. The reason behind this decision is that the current ordering service in Fabric doesn’t guarantee a transaction is ordered, and conceptually a client’s application should not be written differently depending on whether the consensus is crash fault tolerant or Byzantine Fault Tolerant.

Agreement on batches of transactions:

The consensus algorithm provides both safety and liveness under the assumption that up to f nodes are faulty. A consenus round starts by clients that issue requests to all nodes and the current leader batches requests into a proposal and initiates the three stage consensus round at which end all n nodes except up to f of them commit the proposal, or a view change occurs and the proposal is transferred to the leader of the next view.

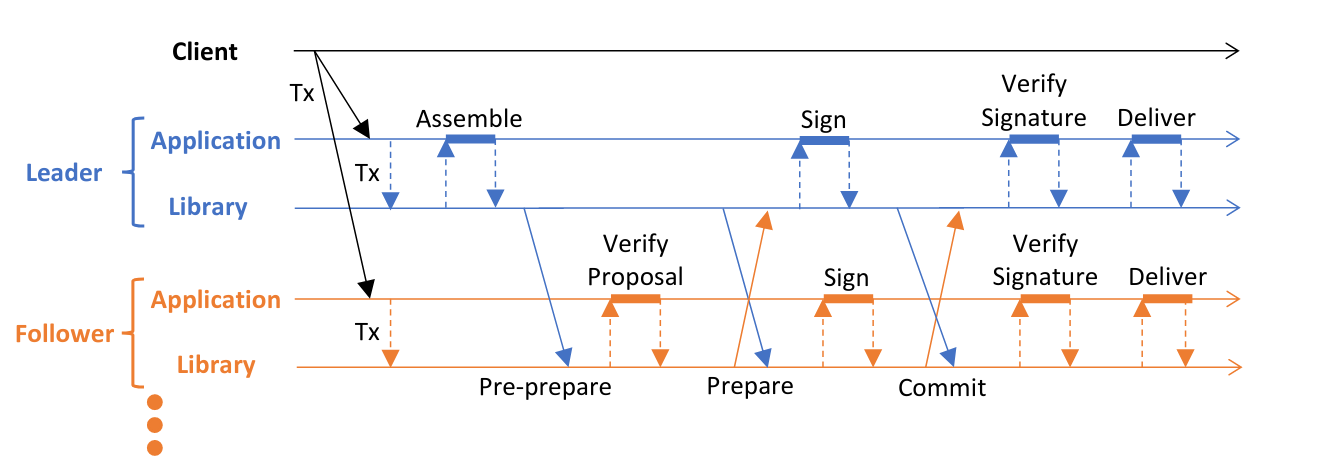

The three stages of the agreement protocol are pre-prepare, prepare, and commit. The pre-prepare and prepare phases are used to totally order requests sent in the same view even when the leader, which proposes the ordering of requests, is faulty. The prepare and commit phases are used to ensure that requests that commit are totally ordered across views.

In the pre-prepare phase, the leader batches requests to assemble a proposal, and it then assigns a sequence number to the proposal. Next the leader sends a pre-prepare message to all followers containing the proposal, its sequence number and the current view number v.

A follower accepts the pre-prepare message if the proposal is valid, it is in view v, it is expecting this sequence number, and it has not accepted a different pre-prepare message for this view and sequence number. Once a follower accepts a pre-prepare message it enters the prepare phase by broadcasting a prepare message. The prepare message contains a digest of the accepted proposal, the sequence number, and v.

Next each node waits for a quorum of prepare messages with the same digest, view v, and sequence number. The quorum size should be big enough to ensure that in the intersection of any two quorums there is at least one correct node. So for example, if n=3f+1 then the optimal quorum size is 2f+1.

After the node is “prepared” it sends a commit message with the same content as the prepare message, as well as a signature on the proposal. Each node collects a quorum of commit messages and their attached signatures. These signatures are later used to notarize the proposal, essentially creating a checkpoint. Upon receiving a quorum of validated commit messages, the node delivers its proposal and the signatures to the application layer for storage and processing.

The quorum size is calculated in the following manner: Let n be the total number of nodes in the algorithm and denote f = ((n - 1) / 3). Then, the quorum is: Ceil((n + f + 1) / 2) where Ceil is the ceiling function. In layman’s terms, the quorum is the minimal set of nodes such that every two such sets intersect in at least 1 honest node.

For example, with 7 nodes, n=7 and therefore f=2 because (7-1)/3 is 2. Notice that with 8 nodes, we still have f=2, because the division (/) is in the integers and not in the real numbers.

With 7 nodes we have an optimal quorum of 5 because it satisfies 2f+1, but with 8 nodes the quorum is 6, because 6 is the smallest group size for which two groups intersect with at least a single honest node (because they intersect by four nodes). Two groups of only five nodes, may intersect in only two nodes and they may both be malicious since f=2.

View change: The view change protocol is inspired by the Synchronization Phase in this BFT-SMaRt paper (illustrated in the attached figure taken from the BFT-SMaRt paper). The view change protocol is comprised of three messages: ViewChange, ViewData, and NewView (Stop, StopData, and Sync in BFT-SMaRt).

The ViewChange message (the first message) is sent to all nodes by some node who suspects the leader is faulty. This message is very lightweight and includes only the next view sequence number. Once collecting 2f+1 ViewChange messages, a non faulty node is convinced that enough nodes consider the leader as faulty, and it will send a ViewData message to the next view’s leader (in practice, it’s the view number modulo the total number of nodes).

The ViewData message is similar to the ViewChange message suggested by PBFT. It is signed, as it will serve as proof in the next phase. The message contains the last checkpoint (last decided proposal) and the next proposal, if it exists, with its state (proposed or prepared). However, as opposed to the PBFT ViewChange message, the ViewData message is sent only to the next leader.

The new leader, after receiving 2f+1 ViewData messages, sends a NewView message to all nodes. This message is similar to the NewView message suggested by PBFT. It includes a proof of the validity of the new view, the 2f+1 ViewData signed messages. The nodes check if they need to catch up with the last decision or if they need to agree on the next proposal, all contained in the NewView message.

Leader liveness monitoring and failover: A Byzantine tolerant consensus algorithm must ensure the liveness of the state machine replication operation in an event where the leader has crashed, is unreachable, or is malicious, for example, censoring client requests.

Malicious leaders may not include client requests in their proposals, or may try to suspend progress by not sending proposals to nodes. To that end, whenever a valid request arrives to a follower - it starts a timer and waits for the request to be included in some proposal. If the timer times out, it sends the request to the leader and resets the timer. Upon a second timeout - the follower suspects the leader, and starts lobbying for a view change to overthrow the leader. The use of two timeouts is as suggested by BFT-SMaRt paper. In the first timeout the client is suspected to not submitting the request to the leader and only in the second timeout the leader is suspected.

However, even if the leader is honest it might crash or simply be disconnected from the rest of the nodes, and therefore cannot broadcast new proposals. If the leader crashes or its communication with the cluster is severed at a time where there is no application traffic, it is imperative to detect this as fast as possible and elect a new leader to prevent availability from being impaired. Hence, the leader is expected to periodically send heartbeat messages to the followers. If a follower hasn’t received a heartbeat from the leader within a timely manner, it suspects the leader has crashed or is unavailable and resolves to start a view change.

Dynamic reconfiguration: The library seamlessly supports addition and removal of nodes without any downtime. In contrast to many consensus libraries which force the application to issue a special command which is replicated throughout the nodes, the library is notified by the application about a reconfiguration through the API which it interacts with it. Since the agreement protocol ensures there is at most a single in-flight proposal at any time (no pipelining), no corner cases (such as a series of proposals with a node addition in between) need to be addressed by complex machinery like no-op proposals to drain the pipeline as proposed in the literature.

Configuration and storage overhead of using the library

Each node in the library derives its configuration from a single configuration object. When embedding the library in a blockchain such as Fabric, it is imperative that when agreeing on a given block, all fields except the node’s identifier would be identical across all nodes.

To that end, the configuration will be saved in the opaque consensus metadata field in the channel configuration](https://github.com/SmartBFT-Go/fabric/blob/release-2.3-bft/orderer/consensus/smartbft/consenter.go#L184-L185).

Except from the configuration, the library also saves some metadata with each block that is committed. The overhead of the metadata is constant and negligible.

Lastly, the library writes blocks received from the leader as well as signatures on commit messages into the Write Ahead Log (WAL), however the WAL can be garbage collected after each block commit, so overall the storage overhead of the WAL can be kept constant and not depend on the size of the ledger.

Embedding the library in a distributed application

The SmartBFT library presentes a minimal interface to the application that uses it:

Input: To submit requests to be ordered, the application that embeds the library (in our case, the Fabric orderer node) invokes SubmitRequest and passes a byte representation of the request.

SubmitRequest(req []byte) error

The library offloads communication to the application that embeds it (the Fabric orderer node, in our case), hence it is the responsibility of the application to feed the messages from other nodes, or requests forwarded from other nodes into the library instance:

HandleMessage(sender uint64, m *bft.Message)

HandleRequest(sender uint64, req []byte)

Output: The library outputs requests in totally ordered batches by notifying the application via a callback:

Deliver(proposal bft.Proposal, signature []bft.Signature) Reconfig

The application is free to implement the callback as it sees fit in order to realize its desired functionality. When embedded inside a blockchain application, the proposal would often denote a block constructed by the leader of that round, and the signatures array would contain a quorum of signatures collected by the library from the various nodes. The Reconfig is an object that allows the application to convey to the library to reconfigure itself (for example, to expand or reduce the number of nodes).

Dependencies:

The SmartBFT library delegates interaction with the external world (communication and storage) to the application that consumes it. It also doesn’t come with its own signature scheme and also assumes its consumer implements it. All such abilities it delegates to the consumer application are termed “dependencies” and their full list can be found here. The dependencies can be categorized into two sets:

Blocking dependencies

A dependency that using it may take an unknown and potentially long period of time, during which the caller goroutine will be unable to take any action.

The Synchronizer dependency is the most prominent one that can block, as it involves waiting for blocks to be received from remote ordering nodes. Another operation that may block, is when sending a transaction to a remote node.

Non-blocking dependencies

All other dependencies can be thought of as non-blocking, and any action that may be prolonged for too much may introduce liveness problems to the consensus protocol.

One important example is the SendConsensus action which is used to send protocol messages by the library. If the library is blocked on network I/O while sending a message to a remote node, the agreement round may get stuck and as a result the followers would start lobbying for a view change to overthrow the leader. Similarly, if some problematic node is causing too many nodes to be blocked on sending messages, it may halt the progress of the entire protocol.

Dependency explanation

Below is a listing of some dependencies the library uses, written in Fabric terminology (transactions, blocks, etc.)

- Assembler: Determines how to package several transactions into a single batch. In Fabric, this batch is an un-signed block.

- Verifier: Determines how to verify transactions and signatures on messages.

- Signer: Determines how to sign messages and blocks.

- Write Ahead Log (WAL): Used for crash recovery and resuming execution from the latest phase in agreement on a block. The SmartBFT library itself contains an implementation of a WAL and the application may choose to use the one provided by the library.

- Synchronizer: Replicates blocks from remote nodes. Used when a node figures out it has fallen behind and cannot participate in consensus because it is missing intermediate blocks.

The SmartBFT ordering service

The SmartBFT consensus library has been integrated into a fork of Fabric which was branched from Fabric version 1.4.x and has been tested and benchmarked. Later on, it was ported to Fabric 2.3.

Integrating the SmartBFT consensus library into a Fabric orderer

High level architecture and component interactions: In its essence, Fabric expects two things from a consensus library: (a) Receiving transactions, and (b) returning them as blocks. The Fabric component that takes care of both aspects is termed a Chain. Each Fabric channel induces its own ledger, and has an instance of a chain that is associated with the bespoken channel.

The current Fabric code architecture supports various implementations of consensus protocols, and as such, it needs a uniform API of creating different types of chains. Fabric achieves uniformity in chain creation via an abstraction that creates chains called a Consenter. A Consenter receives as input an aggregation of abilities also known as a “Consenter support” that the Fabric ordering node can provide to a consensus protocol, such as cryptographic signatures, ledger access, etc. and in turn, and uses a subset of these abilities to create an instance of the consensus protocol, disguised as a chain.

As the ordering service framework RFC states, this approach is suboptimal as it forces the ConsenterSupport interface

to evolve as new consensus protocols are added into Fabric.

To that end, a new type of ordering service node will be created, one that can only run a SmartBFT consensus protocol. Similarly to the existing ordering service, the new ordering service node will posses a chain object per channel. However, it will not use the consenter approach, but rather it would initialize its chains directly as a result of an invocation of the channel participation API. The latter exposes a callback that is invoked when joining a channel, and that callback will be implemented by a component that will fill a role similar to the registrar.

Implementing the dependencies required by the library

In order to integrate the library, the orderer must implement all needed dependencies required by the library. Below we enumerate how the dependencies were realized in the SmartBFT orderer:

- Assembler: The assembler must isolate config transactions in their own batch, as required by Fabric semantics, and construct a proposal that contains an un-signed block.

- Verifier: The verifier ensures that all creators of transactions satisfy the ChannelWriters policy. It also ensures that blocks proposed from the leader maintain the hash chain, and contain only legal transactions. In case of a configuration transaction, it simulates it and rejects if the simulation fails. It is also reponsible to verify consenter signatures.

- Signer: The signer taps into the orderer’s local MSP to sign messages. Unlike Fabric, signature headers do not carry the full certificate, but only the identifier of the node that signed it. This preserves space both in transit and in rest, and in fact despite blocks contain a quorum of signatures, their space overhead is negligible and smaller than the overhead of a Raft node containing a single signature.

- Synchronizer: The synchronizer uses the Fabric builtin block replication infrastructure, but unlike the CFT behavior of the vanilla Fabric, it verifies a quorum of signatures in every block.

- Communication: Both egress and ingress communication pathways completely re-use the newly built Fabric communication infrastructure, as it was designed to be resilient to malicious nodes and is non-blocking. A malicious or slow node cannot effect any other node that communicates with it.

Byzantine majority signature policy

A Fabric block has to be signed by a quorum of consenters, and only by the specific consenters that were defined as consenters during the agreement on that block. When a channel will be created, the configtxgen tool will ensure that the policy is configured to be a Byzantine majority of the orderers defined the channel config. Upon a config change, the BFT orderer will ensure that the block verification policy is derived from the orderers defined in the channel config.

Changes to the peer

While a malicious orderer cannot forge a block, it can deprive a peer from blocks. Hence, receiving the stream of blocks from a single orderer exposes the peer to what is called a censorship attack, or a block withholding attack.

A previous RFC explains at length how this censorship attack is mitigated. In brief, if an orderer or a peer suspects it is being censored, it reaches to other orderers and pulls block headers and their corresponding signatures. Optionally, once in a while, an orderer or a peer may also change the orderer from which it pulls blocks. This approach is different than the approach taken in the SmartBFT Fabric fork, where the peer constantly pulls headers and signatures from several orderers. The deviation is in order to be computationally efficient, as in overwhelming cases, the orderers will not withhold blocks.

Changes to client SDK and Gateway service

Since orderers can be malicious and thus either drop transactions or never include them in a block when assembling proposals, any client that interacts with the BFT ordering service needs to submit the transaction to all orderers. such a change is considered to be trivial and minimal and it is argued that it should be made in every SDK with ease.

Configuration

Configuration can be split into local configuration, that is set by the administrator of the ordering node, and channel configuration, which requires transactions in order to modify the configuration. As its name, the former configuration only influences a node locally, while the latter configuration influences all nodes in the channel.

The local configuration of the BFT orderer inherits from the local configuration of the Raft orderer but only uses the WAL directory configuration key.

The channel configuration contains two aspects:

- Configuration for consenters, which would differ from what is in SmartBFT. Instead of configuring the consenters in the opaque consensus metadata, the consenters would be defined in the global channel configuration.

message Consenter {

uint32 id = 1;

string host = 2;

uint32 port = 3;

string msp_id = 4;

bytes identity = 5;

bytes client_tls_cert = 6;

bytes server_tls_cert = 7;

}

// Orderers is encoded into the configuration transaction as a configuration item of type Chain

// with a Key of "Orderers" and a Value of Orderers as marshaled protobuf bytes

message Orderers {

repeated Consenter consenter_mapping = 1;

}

- Consensus specific configuration stored in the opaque consensus metadata, which contains information on how to instantiate the BFT library.

Upgrading from Raft

Upgrading from Raft will only be allowed (by transaction rule enforcement in the admission path) on channels that are:

-

Already operating with V3.0 capability activated

-

Already have their orderers defined in the global channel configuration.

The latter constraint is to ensure that the orderers can communicate amongst themselves and to minimize human error.

From an operational perspective, the upgrade process from Raft to BFT will be as follows:

-

The channel is put in maintenance mode, to allow only administrative tasks and forbid regular transactions.

-

A representative of the channel gathers signatures on a configuration update from sufficient organizations. The configuration update changes the consensus type to ‘smartBFT’, and sets the metadata to be empty.

-

The configuration update is wrapped into a transaction and is sent to the ordering service.

-

The Raft chain realizes the consensus type has changed, and the Raft chain goes into standby mode which only allows migration forward to BFT but nothing else.

-

The administrators of the organizations communicate out of band and ensure that the previous step has been made across all nodes on all channels.

-

The administrators shut down the nodes and restart them as BFT orderers.

-

The newly spawned BFT orderers observe the latest block in the ledger and figure out it moves the consensus type from something unknown to BFT, and instantiate the library with an empty ViewMetadata.

-

Q: Why do we ensure the consensus metadata in step 2 is empty?

A: An empty consensus metadata will be interpreted as the default configuration, which prevents mistakes in configuring an impractical configuration.

Integration tests

As appropriate for a production grade BFT ordering service, there are numerous intergration tests that test various corner cases such as:

- Crash fault tolerance

- Nodes detecting they are behind due to consensus messages and catching up with the rest of the nodes

- Nodes detecting they are behind based on heartbeats and catching up with the rest of the nodes

- Addition and removal of nodes dynamically without downtime

- A complete removel and replacement of all nodes without downtime

- Leader failover due to request censorship

- Upgrade from Raft to BFT

Performance evaluation

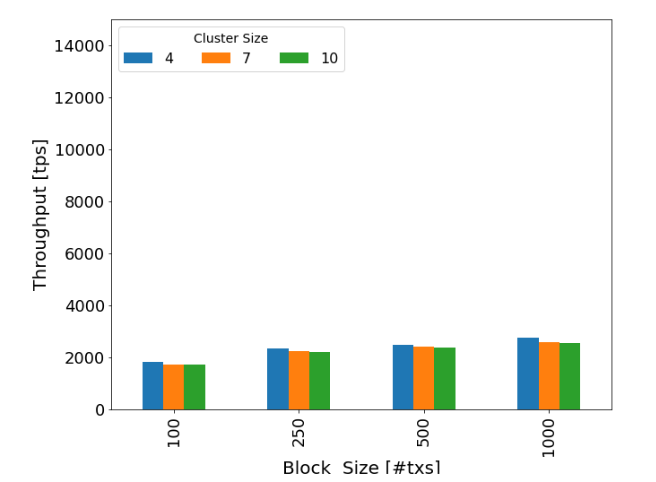

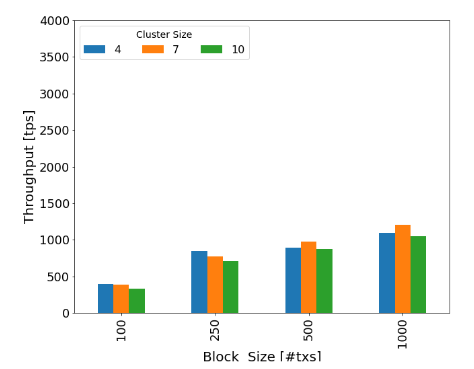

A performance evaluation of the SmartBFT ordering service was conducted. The evaluation examined different cluster sizes and different batch sizes, as well as various geographical locations around the globe. The full performance evaluation can be found in the full paper version. A shorter version of the paper appears in the IEEE International Conference on Blockchain and Cryptocurrency 2021

| LAN | WAN |

|---|---|

|  |

| In LAN, the throughput is above 2000 transactions per second. It can be observed that even smaller batch sizes do not significantly degrede the performance of the system. Furthermore, the size of the cluster also didn’t affect the throughput significantly. | In WAN, nodes were deployed all over the world: Dallas, London, Washington, San Jose, Toronto, Sydney, Milan, Chennai, Hong Kong and Tokyo and with a decent batch size (1000 transactions per block) a throughput of 1,000 transactions per block was achieved. |

Possible questions and their answers

-

Q: Why SmartBFT? There are more performant consensus protocols out there. SmartBFT is essentially a non pipelined PBFT, which isn’t great for performance.

A: By following the approaches explained in the previous two, RFCs in the series, integrating SmartBFT into Fabric does not block any other protocol to be integrated as well. As a matter of fact, it only makes integration of other Byzantine Fault Tolerant libraries easier, as it will surely create re-usable code.

-

Q: Who authored and maintains the SmartBFT library why should we trust it?

A: The SmartBFT consensus library was authored by a group of people from IBM Research, Israel. All of them being contributors to Fabric core, and some of them being maintainers. In mid 2021 its maintenance was transferred to Ideas, the Interdisciplinary Blockchain Research and Expertise center.

-

Q: Can we count on the maintainers of the repository to fix newly found bugs?

A: Since the library is open source (Apache v2.0 license), the current maintainers of the Fabric core can always fork it, update the Fabric dependency and then potentially contribute back to the upstream.

-

Q: Is this library used anywhere?

A: Yes, the library plays the role of a consensus plugin of a fabric fork that is deployed in Atomyze, a platform that tokenizes commodities and runs on top of Fabric.